Continual Learning: Next Paradigm for Intelligence

As models outgrow pre-training and RL scaling, continual learning emerges as the foundation for adaptive, lifelong intelligence.

Intro

In a recent interview, RL pioneer Richard Sutton dropped a provocative claim: LLMs are a dead end. Not because they’re useless—they’re transformative—but because they don’t truly learn from ongoing experience. They predict the next token with uncanny precision; they don’t change themselves because of what just happened. They’re frozen intelligences, brilliant but static.

That position forces us to task: If intelligence means learning from experience, as Sutton has argued, how do we build systems that actually improve while working, that get smarter through completing tasks rather than just executing them?

Our answer: After the great waves of pre-training scaling and RL scaling, the next slope-changer is Continual Learning—models and systems that get better during use. If they truly learn online, they can absorb and recombine the best of human experience even after base weights plateau. From that vantage point, AGI—and eventually ASI—looks less like a moonshot science and more like engineering.

The world’s leading AI labs are likely to quietly bet on this paradigm shift. Ilya Sutskever’s SSI, with its focus on “safe superintelligence,” likely recognizes that safety requires systems that adapt and learn boundaries through experience, not just pre-programmed constraints. The emphasis on “reasoning” at OpenAI and Anthropic points toward systems that should learn from their reasoning processes, which is “test time learn”.

Sutton’s earlier “Bitter Lesson” argued that general, compute-scaling methods ultimately win. Continual Learning is the next such method, but at the system level rather than the parameter level. It’s not about bigger models; it’s about smarter loops.

We periodically host closed-door roundtable discussions on frontier AI topics.

This essay distills insights from practitioner roundtables on Continual Learning across multiple frontier labs and companies. The opinions are synthesized and don’t represent any single organization. If you want to be part of these discussions about AI frontier, apply to join us1. Core Definition: What is Continual Learning?

What Continual Learning IS

Continual Learning is the capability for AI systems to improve through experience—where each interaction makes the next one better. It has three defining characteristics:

Learning from experience: The system’s behavior tomorrow is better because of what happened today

Persistent improvement: Changes apply across time, not just within a session

Self-directed adaptation: The system identifies what to learn, not just follows prescribed training

This manifests through multiple mechanisms:

Online RL: Scalable environments with synthetic data and reward signals

Memory systems: Structured storage that influences future decisions

Test-time adaptation: Real-time behavior adjustment based on recent interactions

Self-curation: Choosing valuable experiences to learn from

Weight/Context updates: Parameter or context modification (optional and debatable, more on this later)

What Continual Learning is NOT

≠ Online RL alone: Online RL is one implementation path, but frequency limits and credit assignment challenges make it insufficient in itself. Updating weights every few hours isn’t the same as genuinely learning from each experience.

≠ Just longer context: Stuffing 1M tokens into context is expensive retrieval, not learning. True learning means the next attempt improves because of the last one, not just because more information is available.

≠ Only personalization: While user adaptation is valuable, the real prize is capability expansion—getting fundamentally smarter, not just more tailored.

The relationship with Meta Learning

Meta Learning and Continual Learning are two interesting topic, related but distinct:

Meta Learning: The ability to rapidly adapt to new tasks with minimal examples (learning to learn)

Continual Learning: The ability to improve continuously through experience over time

Their relationship is synergistic:

Meta Learning could enable Continual Learning: A system that can quickly adapt (meta) can more effectively learn continuously (continual)

Continual Learning benefits from Meta Learning: Fast adaptation means more learning opportunities from the same amount of experience

Think of it this way: Meta Learning is about the slope of adaptation (how fast you learn), while Continual Learning is about accumulation over time (learning never stops). Ideally, we want both, but it’s debatable which goal will achieve first.

2. A case study: Cursor shows what works today

What Cursor actually does

Cursor’s code completion reportedly retrains on ~2-hour cycles using user accept/reject signals as the reward, without separate reward model needed.

Every time you tab-complete or reject a suggestion, you’re training tomorrow’s model. That’s remarkably tight feedback: from user action to model update in hours, not months.

But it’s not quite Continual Learning

Strictly speaking, Cursor implements something closer to off-policy than on-policy RL. The distinction matters:

Off-policy: Collect data from current deployments, batch it, retrain periodically. The model that generated the data isn’t the model being updated in real-time.

On-policy: Immediate updates driven by current policy interaction. The model learns from its own decisions as it makes them.

Cursor batches ~2 hours of data before retraining. That’s fast by traditional standards but still fundamentally batch learning. True online learning would update continuously, perhaps after every interaction or every few minutes.

The lesson for practitioners

Still, Cursor demonstrates three critical principles:

Product exhaust as training data: User interactions aren’t just telemetry; they’re the curriculum. Every click becomes a gradient signal.

Dense rewards work: When feedback is immediate and unambiguous (code works/doesn’t work, user accepts/rejects), learning accelerates. Contrast this with chatbots where “was this helpful?” barely correlates with actual utility.

Tight loops compound: 2-hour cycles mean errors are fixed quickly. Bad patterns don’t persist for weeks. Good patterns propagate fast. The system stays aligned with actual use rather than drifting from synthetic benchmarks.

Practitioners should start with where rewards are thick, feedback is clear, and the environment is controllable. Make it work there, then expand outward.

3. The critical bottleneck: Environment and rewards

Why current systems can’t learn continuously

The key bottleneck is reward signal quality. You can’t learn from feedback you don’t receive, and you can’t improve from signals that don’t correlate with true objectives. Sparse, noisy, or misaligned signals cap learning.

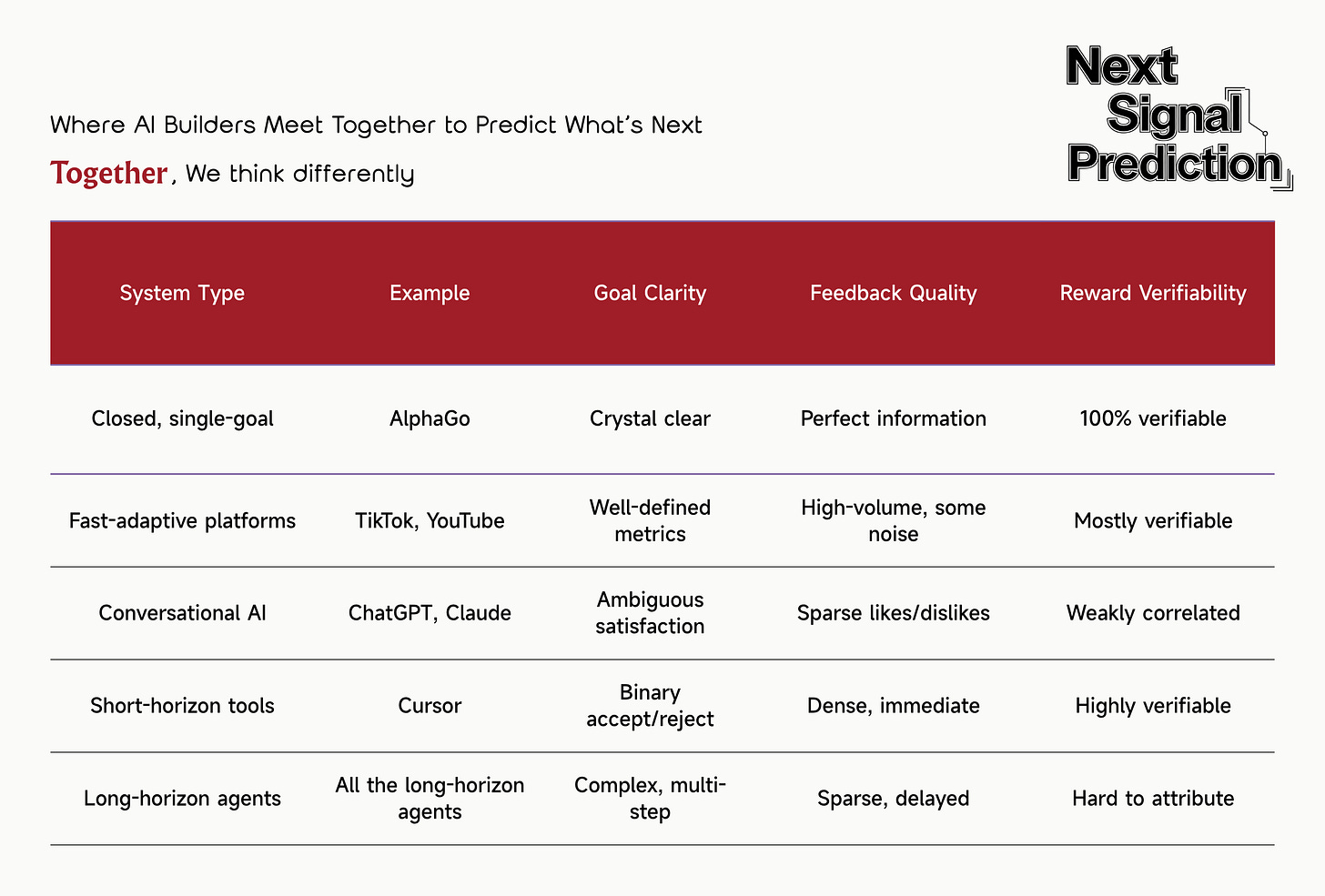

Let’s compare environments by their learning potential:

Why coding is the perfect starting point

Coding emerges as the ideal beachhead for four reasons:

Virtual and controlled: No physical world complexity. Perfect observability. Deterministic outcomes.

Rich verifiable feedback: Code either compiles or doesn’t. Tests pass or fail. Users accept or reject completions.

High interaction frequency: Developers write code all day. Every keystroke is a potential signal.

Clear improvement metrics: Acceptance rate, completion length, bug reduction—all measurable.

Expect the earliest robust Continual Learning in coding, then expansion to similarly structured domains (mathematics, formal verification, systematic analysis).

Beyond personalization to intelligence

Treating the user as the environment opens two paths:

Personalization (the obvious win): Tailor responses to individual preferences, writing styles, domain expertise.

Intelligence leapfrog (the bigger prize): Learn new skills from user interactions. If a user consistently corrects the model’s chemistry, the model should improve at chemistry for everyone.

The key insight: User interactions aren’t just preference signals but also training data. Every correction teaches what the model didn’t know. Every clarification reveals a gap in understanding.

4. The weight update debate: Do we need to change parameters? Where does learning take place?

Two mechanisms for learning

Modern systems have two ways to learn:

In-weights (slow learning):

Traditional gradient updates to parameters

Permanent and durable

Computationally expensive

Shared across all users

Hours to days update cycle

In-context (fast learning):

Adaptation through memory, attention, state

Session-specific and flexible

Computationally cheap

Per-user or per-task

Milliseconds to minutes

The pragmatic answer: Both, strategically applied

The debate isn’t either/or—it’s about routing the right signals to the right mechanism:

Fast adaptation via context/memory: User preferences, recent failures, session-specific patterns

Slow consolidation via weights: Core capabilities, general knowledge, stable patterns

Richard Sutton’s test remains the gold standard: “Is the next attempt better because of the last one?” Whether that happens through weight updates or memory updates matters less than whether it happens at all.

The Sutton test for learning

Richard Sutton proposed a simple bar: “The next attempt is better because of the last one.” Today’s models rarely pass this test without offline updates. They can’t genuinely say “I failed at this approach, so now I’ll try something different based on what I learned.”

Achieving this requires:

Architecture changes: Stateful policies that maintain information across interactions

Memory writes that matter: Not just appending to context, but structured updates that change behavior

Micro-updates: Rapid weight adjustments for critical corrections

Credit assignment: Knowing what to update based on outcomes

Self-directed context engineering

Today’s models passively consume whatever context we provide. Tomorrow’s must actively choose their own context:

What previous interactions are relevant?

Which memories should be retrieved?

What information should be forgotten?

How should experiences be summarized and stored?

This shifts context from a constraint to a capability. Models become their own data curators.

5. Memory is a key machanism

Agent-managed memory

The next step parallels human cognition—agents must manage their own memory:

Selective writing: Not everything deserves remembering. Agents should identify high-value information worth preserving. A correction to a factual error matters more than chitchat.

Active consolidation: Raw experiences should be processed into abstractions. Ten similar coding errors should become one learned pattern, not ten separate memories.

Strategic forgetting: Outdated information should be pruned. Wrong assumptions should be overwritten. Irrelevant details should fade.

Smart retrieval: Memories need smart retrieval. The right memory should surface at the right moment, not through exhaustive search but through learned associations.

This isn’t a database. It’s a dynamic learning system that evolves through use.

The inefficiency of “just add more context”

“Just append more context” burns compute without learning. Processing 1M tokens of conversation history on every turn is like a student re-reading all their notes before answering each question—inefficient and unscalable.

Instead, write selective results into memory so future inferences start smarter:

Summarize key insights, not full transcripts

Store patterns, not raw examples

Maintain statistics, not individual data points

Update beliefs, not just accumulate evidence

6. New evaluation paradigms: Measure learning slopes

Static metrics miss the point

In Continual Learning, inference process includes learning. Static benchmarks miss the point. What matters is how quickly systems improve, not just their final performance.

Thus, the optimization objective of continual learning is more like the derivative of the loss function (instead of the loss function) with respect to interaction count. We care about ∂Performance/∂Experience, not just Performance.

We propose some potential eval setup and metrics here, and would love to hear more ideas from the community:

Cold-start adaptation speed:

Deploy a new feature

Measure user satisfaction after 10, 100, 1000 interactions

Plot the improvement curve

The slope matters more than the starting point

New-game benchmark:

Present an unseen environment (new game, new domain, new task type)

Fixed interaction budget (e.g., 100 episodes)

Measure the learning curve, not just final performance

Strong Continual Learning shows steep initial improvement

Meta-learning test:

New task → 5 examples → Measure performance

New task → 50 examples → Measure performance

Compare the 5-shot vs 50-shot gap

Smaller gaps indicate better meta-learning

7. Architechture: lessons from recommender systems

The recommendation system precedent

Recommender systems have run minute-scale updates for years, but mostly in non-end-to-end pipelines. They are systems that try to mimic continual learning. The typical architecture:

Recall (millions → thousands) →

Ranking (thousands → hundreds) →

Final scoring (hundreds → dozens) →

Recommendation feedThe fatal flaw: Final rewards (user clicks) primarily updated only the last stage. Upstream modules starved for signal. The ranker improved while recall stagnated.

The end-to-end imperative

LLMs succeeded partly because they’re end-to-end. One model, one objective, gradient flows everywhere. Recommenders are finally following suit, moving toward unified architectures where user feedback can improve every component.

Key lessons for Continual Learning:

Short feedback loops are mandatory: If reward takes hours to propagate, its teaching value evaporates. The model forgets what decision led to what outcome.

End-to-end raises the ceiling: When credit flows to all components, system-wide optimization becomes possible. No module becomes a bottleneck.

Unified architectures scale better: Fewer interfaces mean less information loss. Single models are easier to update than pipelines.

The compute reality check

Long-context brute force is often non-learning—it’s expensive retrieval masquerading as intelligence. Processing 1M tokens repeatedly doesn’t make the model smarter; it just makes inference expensive.

Prefer designs that convert interaction compute into persistent state changes:

Memory writes: Crystallize insights for future use

Weight consolidation: Periodically compile important patterns into parameters

State compression: Summarize experiences into efficient representations

Selective attention: Focus compute on learning, not re-processing

The goal: Each interaction should make future interactions cheaper and better, not just longer.

8. Open questions and research frontiers

The big unknowns that could unlock everything:

Architecture: How do we inject rewards into fast weights efficiently?

Can attention mechanisms learn without gradients?

What state representations support rapid adaptation?

How can memory updates approximate weight updates?

Exploration: How do we enable task-free exploration without reward hacking?

Can curiosity be designed as a robust reward?

How do we balance exploration vs exploitation online?

What constitutes “interesting” for an AI system?

Credit assignment: How do we generalize credit across heterogeneous components?

Through chain-of-thought reasoning steps

Across tool use and API calls

Between memory, weights, and context

Over extended time horizons

Scaling dynamics: What are the scaling laws for Continual Learning?

Does performance scale with interaction count like scales with parameters?

What’s the optimal ratio of online to offline learning?

How do we prevent catastrophic forgetting at scale?

9. Three eras of iteraction

Where we’ve been and where we’re going

We’re witnessing a fundamental shift in how AI systems interact with the world:

Chat era: RLHF made conversation pleasant. We optimized for helpfulness, harmlessness, and human preference. The interaction was reactive—user asks, model responds.

Long-reasoning era: RL unlocked deeper chain-of-thought. Models could trace through complex problems, maintain consistency across extended reasoning, and produce expert-level analysis. But still fundamentally responsive to human prompts.

Agent era: Systems must self-explore and self-harvest rewards for open-ended goals. The model becomes proactive—identifying problems, gathering information, experimenting with solutions, and learning from outcomes.

The decisive milestone: Task-free learning

The environment persists, but tasks are self-generated. No human needs to say “solve this problem.” The system identifies what’s worth learning, designs its own curriculum, and pursues knowledge for its own sake.

Imagine deploying a system with access to scientific literature and simulation environments. Without being told to cure cancer or design better batteries, it starts identifying promising research directions, running experiments, and accumulating insights. That’s task-free learning.

With strong meta-learning, every interaction becomes a learning opportunity. Every environment becomes a classroom. Every failure becomes data.

Conclusion: From static models to living systems

Pre-training gave us powerful pattern matchers. RL added goal-directed behavior. Continual Learning creates living systems—entities that evolve through use. The distinction is fundamental:

Static intelligence: Brilliant but frozen at training time

Living intelligence: Continuously improving through experience

We’re moving from models that can answer questions to systems that can learn from their mistakes, adapt to new domains, and discover knowledge we haven’t imagined.

The destination isn’t only more parameters. It’s better slopes: systems where the default outcome of interaction is improvement, not just output.

Start where rewards are clear. Push toward agents that propose their own tasks. When a system gets smarter because it tried and failed, when it remembers what works and avoids what doesn’t, when it seeks out challenges to overcome—then we’ll know we’ve crossed the threshold.

Continual learning is how we go from models that recite existing knowledge to systems that generate new knowledge.

Welcome to the age of Continual Learning.